The German philosopher Walter Benjamin wrote in 1931 in his short essay "Unpacking my library", that collecting was an important gesture, because it means giving importance to things, implementing a sort of transfiguration in them and inserting them in a context different from the immediate and often banal way in which we encountered them in everyday life. A way of thinking and referring to things that completely departed from the canons of consumerism and also from mass culture. Despite having to do with the possession of objects and their purchase, Benjamin's collecting moves away from the logic of status or mere economic "business" to become a very personal, almost sentimental experience. According to Benjamin, this mechanism has the advantage of erasing the commodity character of things, transforming them into wonderful objects of desire capable of evoking not only memories, experiences and emotions, but even entire existential worlds.

I couldn't have found a better justification for my collection of CDs and LPs, which also includes the complete works for microtonal electric guitar by the Norwegian composer Bjørn Fongaard, an exponent of that exponential growth of Northern European artistic music, which developed in the second half of the 20th century.

Most of the Nordic musical activity during this period, the result of the achieved political, economic and social stability in Europe and the United States, can be attributed to the numerous Danish, Swedish, Norwegian, Finnish and Icelandic composers born during the twenty years following the Second World War world. In the early 1960s, a new phase could be observed in the ongoing modernization of the musical language in post-war Norway. The dominant hegemony of neoclassicism was followed by a period of time in which expressionism and a kind of neo-romanticism gained importance. This phase did not only involve a change in musical styles, but also a profound reorganization of the role of music in society. Primary activities of the Norwegian government, after the Second World War, were the formation of a modern society, with the reconstruction and modernization of the nation: these projects also included plans regarding the arts and music to offer better conditions for artists and expansion of already established institutions, as well as creating new ones. This included, among other things, the development of opera, the music education system, symphony orchestras, etc.

The realization of these plans took quite a long time, as it was only in the late 1960s and early 1970s that many of them began to be implemented or initiated. Society had changed significantly during these years, so that the goal of developing musical culture was no longer the only concern of these projects. Early plans were based on the idea of having major music institutions located in the capital, Oslo, to be of service to the rest of the country. It was thought that in this way musical education, opera, orchestras and ensembles could reach even the most peripheral regions through individual and group tours. Changes in public opinion occurred, with strong political controversies over the relationship between center and periphery. This led to a growing concern to make the peripheral regions similar to the situation in the capital. The government began to pay some attention to art and music, encouraging more widespread distribution, investing in and professionalizing local institutions such as conservatories and orchestras, and offering better opportunities for professional experiences in peripheral districts. The central institutions were still considered to be of a higher standard, but the result was an improvement in the professional culture and institutions both locally and in Oslo.

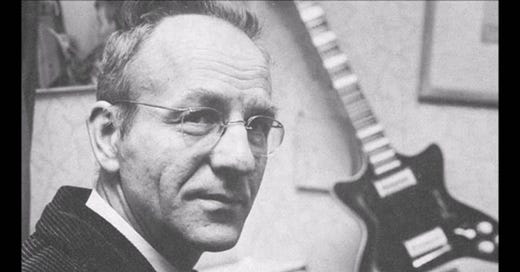

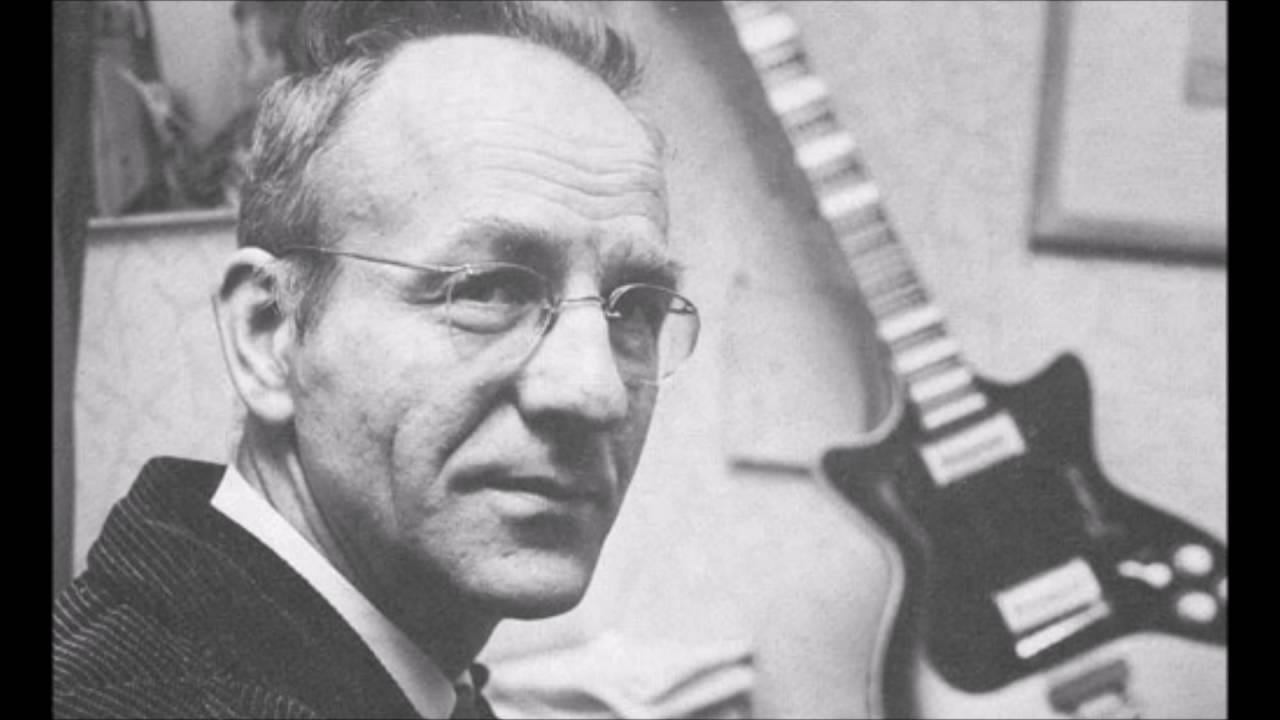

In this cultural ferment the music and style of the composer Bjørn Fongaard (Oslo 1919- Oslo 1980) was born. Fongaard studied at the Oslo Conservatory of Music where his teachers were Per Steenberg, Sigurd Islandsmoen, Bjarne Brustad and Karl Andersen. An accomplished musician, for many years he was better known as a guitarist than as a composer. Influenced by modernists such as Hindemith, Schoenberg and Webern, Fongaard managed to develop a very personal style of experimental composition, extremely linked to the electric guitar. A style so advanced that when it came to performing his composition Uranium 235 for orchestra in 1965, none of the musicians were able to read the new and unknown notation.

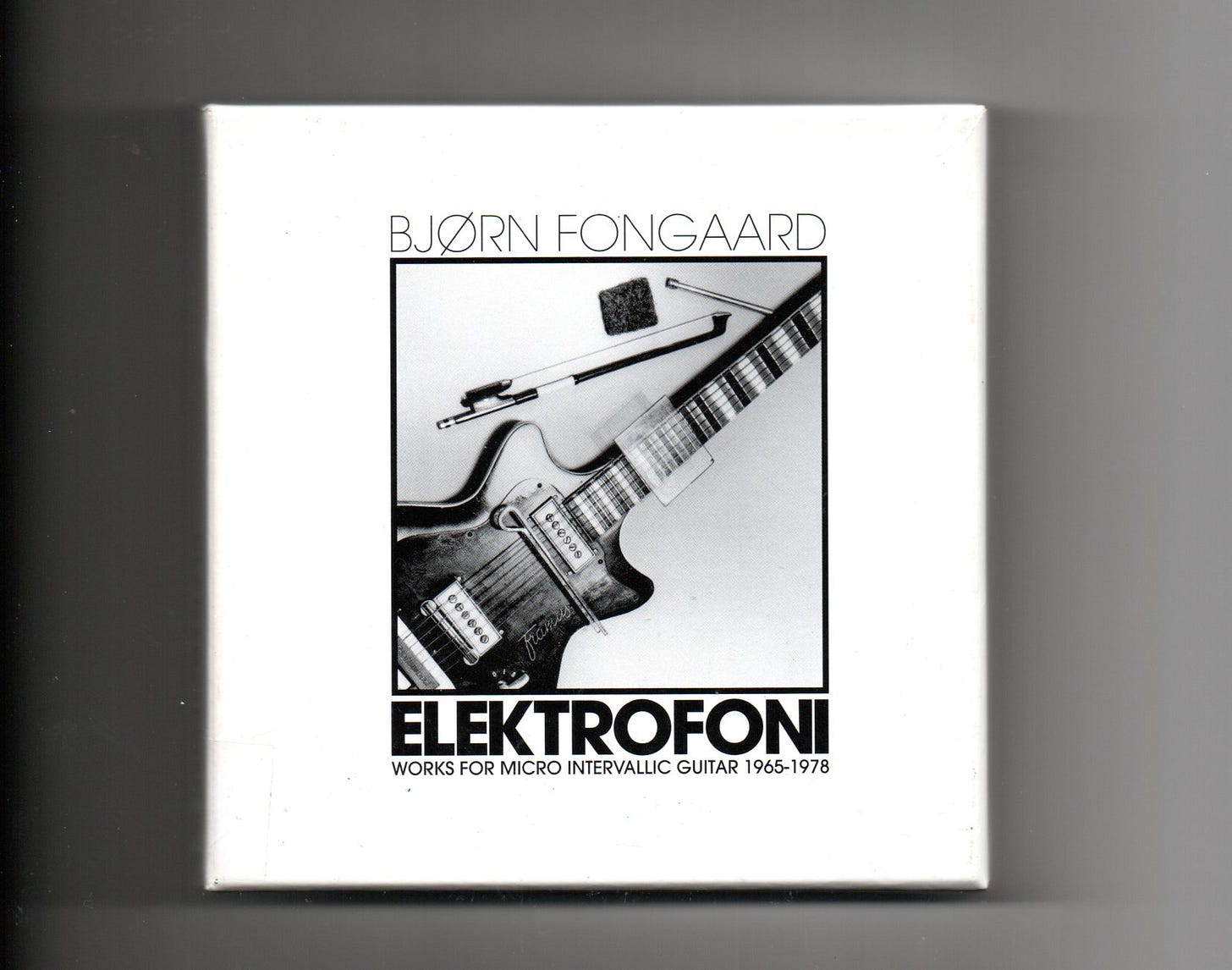

Disappointed by this situation, Fongaard decided that he could just as easily perform his music on the guitar, an instrument he had studied for experimental purposes for a long time. Having acquired a Framus electric guitar (model 5/131 Hollywood, solid-body with two pick-ups), he radically modified the fretboard, adding frets designed to produce quarter tones. Fongaard positioned the guitar horizontally to play and prepare it in an atypical way through the use of small bows and various objects. From this point of view, perhaps he was the first to explore the potential of the prepared guitar. For this instrument tuned with microintervals he composed a series of works, both solo and in combination with percussion and narrator. The titles reveal the composer's interest in philosophy and astronomy: Galaxy, Homo Sapiens, Genesis. His Sinfonia Microtonalis represented Norway at the 1970 International Rostrum of Composers in Paris. He has also attempted to transfer his microtonal principles to orchestral works including Orchestra Antiphonalis, Symphony of Space, Universum and Mare Tranquilitatis.

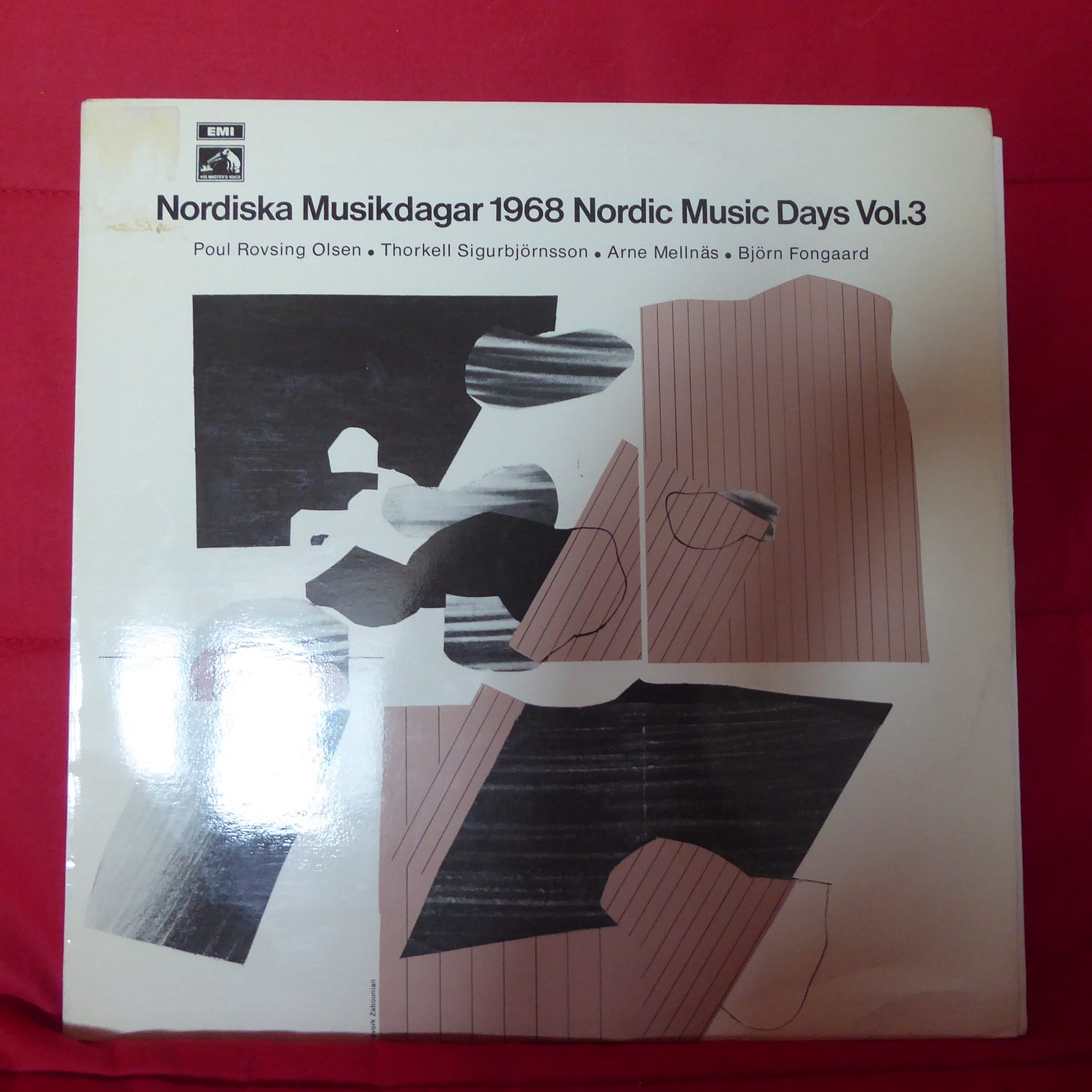

I encountered Fongaard's music by chance, buying this LP a few years ago, “Nordiska Musikdagar 1968 Nordic Music Days Vol.3”, released in 1969 by EMI, where Fongaard is present with his piece “Homo Sapiens”.

The notes on the back of the album cover read: “The composer writes on his work: Homo Sapiens was composed in 1966 and first performed by the Norvegian Broadcasting Corporation in the same year. This is a purely instrumental work, composed for and performed on a micro interval guitar. These sounds sources, which resemble the electronic tonal qualities, are produced solely by means of a specially worked out instrmental technicque: and as they are very weak they can be ampplified by the use of ordinary loudspeakers. The source of inspiration for this work is the man's own history of development and progress. The work as a whole is animated by the wish that peace and brotherly love may continue to fine dmore and more room in people's hearts. The formal division is apparent in small episodes and rhythmically monotonous beats which symbolize humanity's restless course in the future,until we stop questioningly at our own time.”

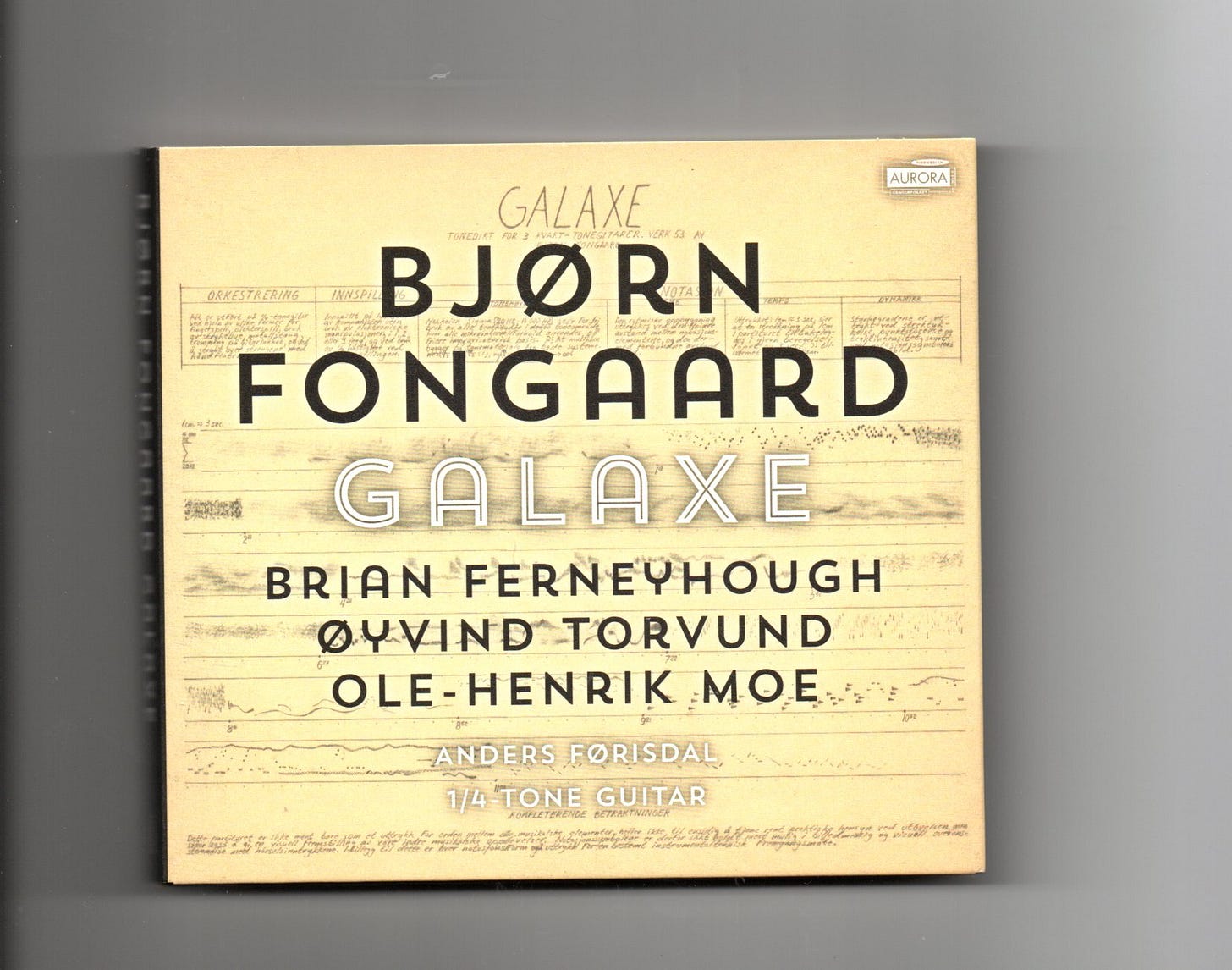

A very interesting piece that pushed me to delve deeper. Unfortunately Fongaard's music isn't performed much and is little known, so it took me some time to get my hands on the double CD, “Galaxe”, a new recordings by Norwegian guitarist Anders Førisdal, released in 2015 on Aurora Records

and on the splendid monographic collection “Elektrofoni: Works For Micro Intervallic Guitar 1965-1978”, a fabulous box set of CDs and DVDs, which collects his rich musical production, produced in 2010 by the Norwegian record company Prisma Records.

Particularly striking are “Galaxe” op. 46 (1966) for three electric guitars, one of Fongaard's best-known works. The title reflects Fongaard's strong interest in nature and modern science, something that is also highlighted by titles such as Kosmosyntese (Cosmo-Synthesis) and Science Fictions. The piece is composed of twelve sections with very different characteristics, connected with a sort of codicil writing: generalized patterns that can be extremely short or extended beyond recognition, which represent an extremely heterogeneous musical vision.

Fongaard had previously employed morse code in Uranium 235, and it is not unlikely that some of the material in Galaxe also refers to that code language.

In the Improvisations op. 81 (1968) the material is much less opaque than in Galaxe, more like a classical movement. The work's fourteen sections are all based on a phrase with a similar shape: two tones, three tones, two tones, and a concluding wave pattern. Due to the arrangement of instrumental sounds and the variety of textures and tempos, this simple form seems to increase the possibilities for exploring timbral variations rather than limiting their expressive possibilities. The overall form shows a clear balance of connections and contrasts, and after the free expression of the first seventh sections, the extended resonances of the eighth section set in motion a development that extends into the orchestral finale.

Perhaps to pass the time between Galaxe and Improvisations, Fongaard wrote several small works in three movements: Aphorims op. 61, Novations op. 62 and Aphorism op. 63 of 1967. The arrangement of sounds and instrumental techniques is an important element in these works and varies from movement to movement in the different pieces. Unlike the other works on the double CD "Galaxe", these pieces are all notated in a traditional score format with the sounds or techniques used (sponge, metal rod, bow, strokes on the instrument, etc.) noted on a separate system. ). Operation. 61 and 63 are written for a single performer, while the op. 62 is meant to be made on tape. In the op. 63, the percussion instruments and the voices of the performers are included in the instrumentation.

Symphony Microtonalis no. 1 is the exact opposite of the op. 62 and indicates the numerous pieces for solo instrument and tape that Fongaard wrote in the Seventies. Characterized by a relatively extended form, it is related to Galaxe, although it features a sound from the first composition. The piece is written to be made in the studio using tape at double or half the normal speed, and the score is designed to give an overview of the form to help the engineer assisting in the recording. The notation provides verbal instructions for what type of sound or technique to use in a given section of the piece for the four different tracks.

It seems that Fongaard intuitively understood how the electric guitar, due to the microscopic sensitivity of the microphones capable of amplifying otherwise unrecordable sounds and nuances, is a truly electronic instrument and not just an extension of acoustic string instruments. Fongaard's music therefore represents a space in which "terrestrial" and cosmic harmonies "meet without ever having been united. Norway has never been so interesting.

Bibliography

Sergio Sorrentino, La chitarra elettrica nella musica da concerto: La storia, gli autori, i capolavori, Arcana, 2020

Frederick Key Smith, Nordic Art Music: From the Middle Ages to the Third Millennium, 2002

John D. White, New Music of the Nordic Country, 2002